I’m about to give vent to my contrarian side. Before I do, though, let’s consider what civilization was like when Gautama Buddha began teaching and as Buddhism spread throughout South, Southeast, and East Asia.

Siddhartha Gautama was born in the foothills of the Himalayas in what’s now Nepal, near the border with India. He taught there and in the Ganges Plain and acknowledged spiritual roots in the Indus Valley. It’s generally believed he lived for an 80-year span between 560 and 400 BCE.

We can’t know the texture of day-to-day life there and then, but it was an area of the world undergoing what then would be considered rapid change. The urban centers of the Indus Valley had collapsed, leading to a population shift eastward toward the Ganges Plain, where settlements were smaller and more widely dispersed. Tribal kingdoms were being absorbed into state formations.

The Vedic period was giving way in philosophy and religion. Spiritual life was rich and complex, with many mendicants wandering the plain and teaching practices to end rebirth and suffering. The Buddha studied with at least two of those and became one himself, a highly successful one. Upanishads were composed in that era, and modern Hinduism emerged, as did Jainism.

Along with these cultural changes came oppressive rulers, caste-based cruelty, exploitation of ordinary people during wars, banditry, and draconian punishments for even minor crimes. Natural disasters, epidemics, and wild animals also posed an ever-present threat to human safety.

The phrase “Life is tough, and then you die” comes to mind. Life was indeed tough, and the culprits making life so difficult were demons and a pantheon of deities, often related to forces of nature. That helps explain the background of the Metta (Loving-Kindness) Sutta. Here’s what I wrote previously about the sutta’s back story:

What led the Buddha to say these particular words [teaching kindness] fascinates me. He addressed a group of monks who had gone into the forest to meditate during the rainy season but were scared off by the devas (celestial beings) in the trees. The monks returned to the Buddha, who had no other location to suggest.

The Buddha sent them back to the forest after teaching them the Metta Sutta, which they then recited and practiced in the woods. That made the devas realize they had no reason to scare off the monks again. The monks remained in that forest throughout the rainy season and returned to the Buddha as enlightened beings.

The Buddha was a master at addressing people where they were, not where he thought they should be. Did he believe that devas were making threatening sounds and playing tricks on the monks to get rid of them? Or did he use the sutta to relax the monks and build their confidence? Either way, he taught them how to be more loving, not how to scare the demons away by being more fierce. He taught them:

Let one not deceive nor despise another person, anywhere at all. In anger and ill-will, let him not wish any harm to another. Just as a mother would protect her only child with her own life, even so, let him cultivate boundless thoughts of loving kindness towards all beings. Let him cultivate boundless thoughts of loving kindness towards the whole world — above, below and all around, unobstructed, free from hatred and enmity.

Now, here comes my contrarian side.

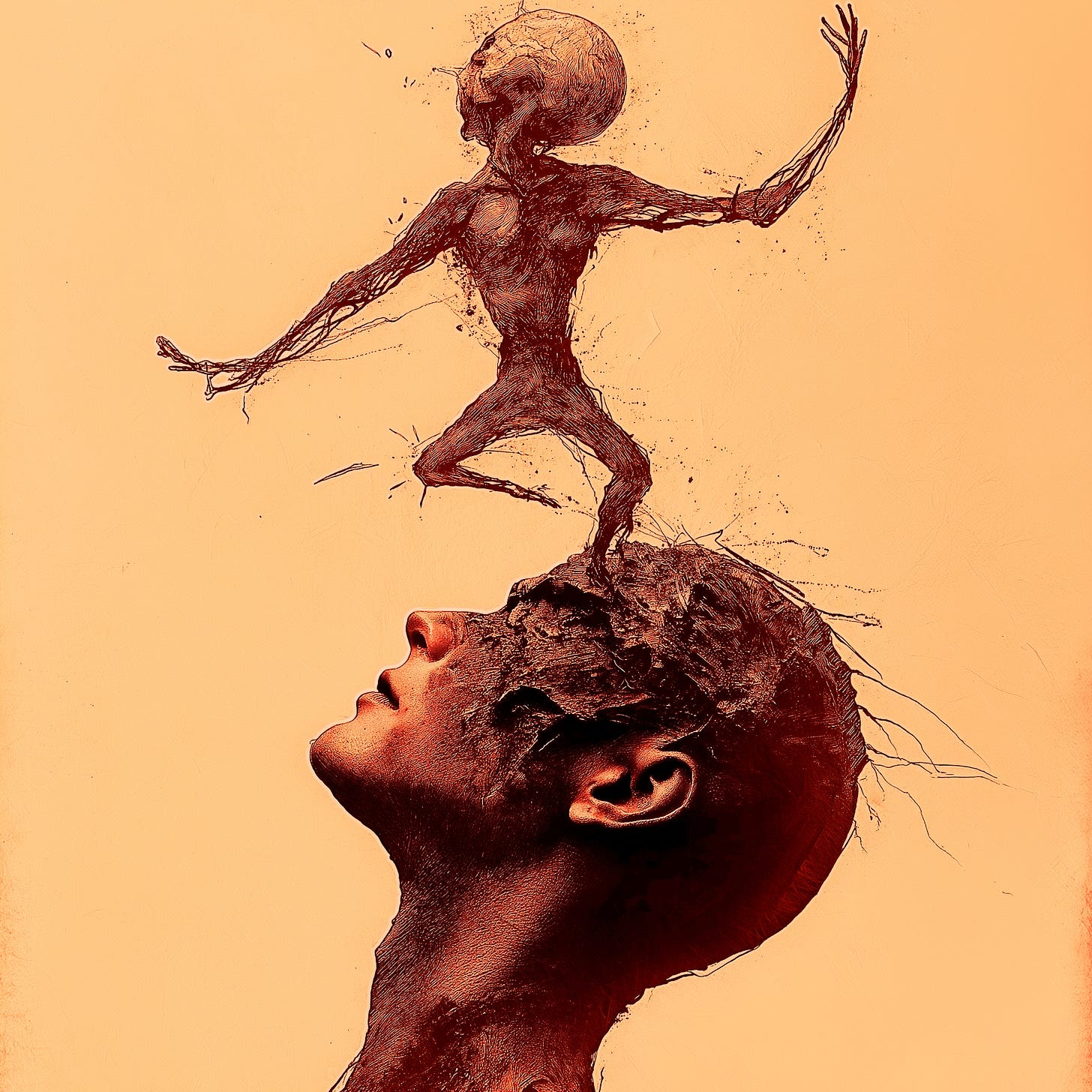

For many centuries after Gautama Buddha passed into parinirvana, people continued to believe in demons, but the language used to defeat demons became more warlike—and that language remains in liturgies we venerate even though we realize that the real enemies are “our own projections and misdeeds.”1

Consider this quatrain from the Wheel of Sharp Weapons,2 attributed to Dharmarakṣita, as translated by Thubten Jinpa:

My ill temper is intense, my paranoia more coarse than everyone’s; Hard to befriend, I constantly provoke others’ negative traits-- Dance and trample on the head of this betrayer, false conception! Mortally strike at the heart of this butcher and enemy, Ego!

I added the emphasis on the final two lines, which are repeated 37 times in Dharmarakṣita’s 116-verse teaching.

Here’s another line:

Strike him, strike him, pierce the heart of this enemy, the self!

Maybe I’m picking on Dharmarakṣita, who lived in the Ninth Century. Still, the translator is a respected current teacher who says he’s especially proud of this translation, and the work is widely used.

I agree that a grasping ego is a block to awakening, but I prefer to say I “let go” of mine—the grasping aspect. If I had obliterated any ego, I wouldn’t be writing these words. And if Thubten Jinpa had no ego at all, would he have put in all the hours needed to translate the Wheel of Sharp Weapons? I may have the opportunity to ask him that later this month.

I can’t begin to count how often words like “fierce” and “wrathful” are used in Tibetan teachings. Again, I understand why they’re in the original literature, but I’m giving vent to my inner curmudgeon to remind us that if Buddhism is to flourish in the West, perhaps we need to return to a more loving language like that in the Metta Sutta.

From the Pure Land has subscribers in 28 U.S. States and 10 countries. The podcast has listeners in 24 countries. Consider:

Becoming a subscriber if you are not one already. Free and paid subscribers receive the same content, but subscribing for $5 a month or $50 a year helps support my mission.

Making a one-time gift of any amount.

Sharing this post with a friend.

Language from the commonly chanted Dedication of Merit to Universal Enlightenment.

Share this post