Somebody comes into the Zen center with a lighted cigarette, walks up to the Buddha statue, blows smoke in its face, and drops ashes on its lap. You are standing there. What can you do? —From Seung Sahn’s book Dropping Ashes on the Buddha

This famous koan from Korean Zen master Seung Sahn (1927-2004) is intended to help students separate the iconography from the person of the Buddha and the person from the teachings. Stories abound in Buddhist lore about the righteousness of using a Buddha statue for firewood or chipping off gold plating to help the poor.

There’s no record of the Buddha telling his followers not to make images of him, but in the Vakkali Sutta as translated by Bikkhu Bodhi he said this to a dying monk who regretted not traveling more often to see him:

Enough, Vakkali! Why do you want to see this foul body? One who sees the Dhamma sees me; one who sees me sees the Dhamma. For in seeing the Dhamma, Vakkali, one sees me; and in seeing me, one sees the Dhamma.

The Sanskrit word dhamma and the Pali word dharma mean the Buddha’s teachings and can also be understood as how the world works. By living in the dharma, we are “seeing,” or being in contact with, the Buddha no matter where or when we are.

Thich Nhat Hanh expressed a thought like this this in a poem to a dying friend called Contemplation on No-Coming and No-Gong, which begins:

This body is not me. I am not limited by this body.

The Buddha is similarly not contained in the images and symbols used to represent him. We don’t know if that’s why there were no images of the Buddha until five or six centuries after his death. Symbols like a dharma wheel, an empty throne, footprints, or a bodhi tree represented the Buddha and his teachings.

It was when Buddhism became a more structured religion and philosophy and spread along the then-developing Silk Road that depictions of the Buddha in bodily form began to appear. One of the first depictions is in the frieze on a small gold reliquary found in Bimaran in eastern Pakistan in the 1830s. Its creation has been dated to the First Century, more than 500 years after the Buddha’s death, and it was found more than 600 miles from where he lived.

Bimaran is part of the Gandhara region, where other examples of early Buddha figures and Buddhist art are found. It is also a region invaded by Alexander the Great and brought under his control only two centuries after the Buddha’s death. Some of the earliest Buddha statues show Greek features and wavy hair, along with the third eye and elongated earlobes.

The third eye represents wisdom—the ability to see beyond what others see. The elongated earlobes have been given all sorts of symbolic meanings (compassion, listening) but most likely are an acknowledgment of Siddhartha’s privileged early life. Men of his class wore jewelry that stretched the earlobes—jewelry he would have removed when he became a renunciate.

A recent article in Buddhistdoor Global (BDG) explores the Greek influence on Buddhist art and the possible influence of Buddhism on Alexander the Great and early Greek culture.

We can’t know with any degree of certainty what the Buddha looked like just as we can’t know what Jesus looked like. The first images of the latter, dated to around 235, were found in Syria. As each religion spread, images of the man regarded as its founder took on the characteristics of the ethnic groups in the areas where it was flourishing.1

That’s not surprising. Nor is the way religions adopt some elements of local belief systems as they spread to new areas. Buddhism is not flourishing enough yet in the West to see non-Asian and non-Greek-influenced Buddha images. Just for fun, I began thinking of what a Western Buddha image might look like, and an Idea popped into my head.

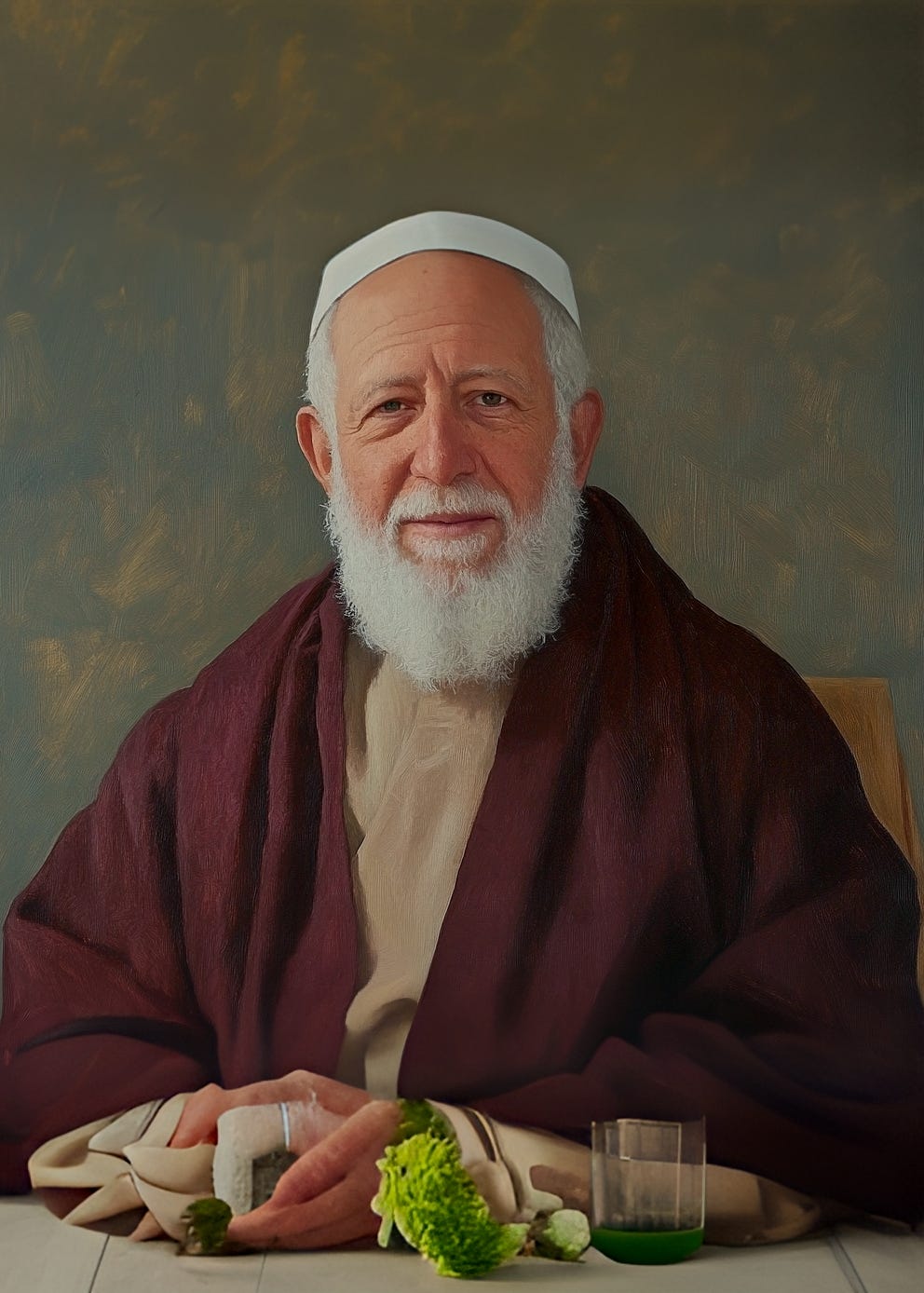

Because so many Western Buddhists have Ashkenazi Jewish backgrounds, could it be considered flourishing among us? If so, might a Buddha with Jewish facial features be the first decidedly non-Asian-looking Buddha image? I asked two of my AI imaging assistants to come up with one, and this was the best they could do:

I’m joking, of course, about a Jewish-looking Buddha, but I’m seriously addressing the question of what’s holy. I believe holiness is in the truth of the teachings, not in any particular image or practice. In the West, I hope we can experiment with the images and practices without in any way detracting from the holiness of the teachings.

For me, the teachings have led me to understand that I already live in a Pure Land, so everything is holy now, as Peter Mayer so eloquently explains in his song:

From the Pure Land has thousands of readers and subscribers in 38 U.S. states and 17 countries, and the podcast has thousands of listeners in 54 countries.

The Buddha emphasized the joy of giving. Dana is not meant to be obligatory or done reluctantly. Instead, dana should be performed when the giver is “delighted before, during, and after giving.” —Gil Fronsdal.

Consider being delighted by paying for your subscription even though you’ll receive the same regular content as those with a free subscription. For $5 a month or $50 a year, you’ll contribute to Mel’s expenses and see parts of his book Slicing and Dicing Buddhism as it progresses.

Share this post with a friend.

Listen and subscribe to the From the Pure Land podcasts via your favorite app or by clicking here.

My uninformed impression is that the process slowed down for Jesus images as Christianity flourished in places like Africa and some Asian nations.