Lama Surya Das tells students that his goal is not to help them become Buddhists but to help them be Buddhas. He also says that if he were now writing his most famous book, Awakening the Buddha Within, he’d alter the title a bit because the Buddha within is already awake. We must be deeply and experientially aware of that to live in our Buddha Nature.

Our true Buddha Nature apprehends the world clearly in its nondual state, in which we are all one — or so intimately interconnected that we might as well be one. Along with the clarity of that inherent Buddha Nature comes profound wisdom, boundless compassion, loving-kindness, and release from churning thoughts that promote bias and hate toward ourselves and others.

We can’t access the Buddha Nature within by thinking about it or reading about it because it is not a thinking or a doing entity. It’s an experiencing and a being entity. Please be aware that my writing is a layperson’s attempt to put profound beliefs into inadequate words. The Buddha within is not an “entity,” but its state probably can’t be summed up verbally, so “entity” is the noun I came up with.

In Buddhism, we — all sentient beings — are born with a permanent purity that’s temporarily clouded by confusion. In Gautama Buddha’s words:1

[The] mind is originally radiant and clear, but because passing corruptions and defilements come and obscure it, it doesn’t show its radiance.

In my understanding, the “passing corruptions and defilements” — in modern, informal English — are misconceptions and confusions that hold us in a dream state we can awaken from. In this state, we are separate and apart from each other. We desire to awaken from our dream of fog and clouds to what some Buddhists call the luminous sky-like nature of mind.

It's time for a deep breath, readers. That may be a lot to absorb for some of you, but even if it’s familiar, take a breath anyway.

Buddhism teaches that we are all born pure, loving, and compassionate beings lost in confusion that can be dispelled.

Two famous stories in the faith's lore are about Aṅgulimāla in the Buddha’s lifetime (6th or 5th Century BCE) and Milarepa in the 11th and 12th Century. Each man was a mass murderer before practicing the dharma (the teachings of Gautama Buddha), and each became a realized master. Their stories are fascinating, but I’ll leave them for another time.

To this day, in some Asian cultures, Aṅgulimāla plays the role a saint might play in some Christian cultures — the patron of childbirth and fertility. Milarepa is read widely and revered worldwide as an early figure in teaching Mahamudra, which I have written about, and in the Kagyu lineage, which Westerners might call the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism.

If a mass murderer can become a Buddha, so can you and I, regardless of our faith. We already are buddhas, but most of us don’t know it because the fog of confusion travels with us everywhere.

I’ve heard at least one Buddhist teacher suggest that non-Buddhists might attain some level of enlightenment but not full enlightenment or full Buddhahood. That’s an example of Buddhist exceptionalism, a term used by Evan Thompson in his book Why I Am Not a Buddhist. Although Dr. Thompson calls himself a “good friend of Buddhism,” he’s critical of what he sees as modern trends that set it apart from any other religion.

I don’t accept Buddhist exceptionalism just as I don’t accept all the directions other faiths have taken. Still, the dharma teaches me that we’re quick to feed our egos by focusing on the differences between ourselves and others. I think the same can be said for our faiths. As Muhammad Ali said:

Rivers, ponds, lakes, and streams — they all have different names, but they all contain water. Just as religions do — they all contain truths.

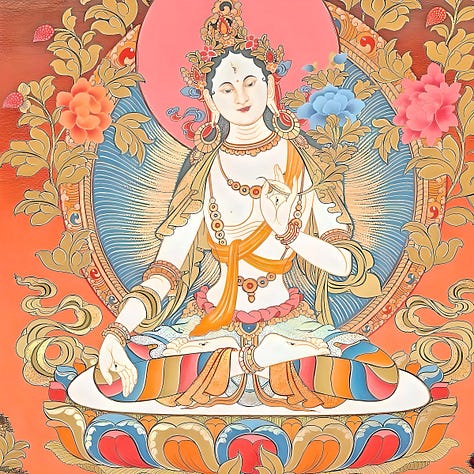

Regarding our relative degrees of enlightenment, we all in the human realm continue to have flaws and fall somewhere short of complete buddhahood. That’s one reason we’re encouraged to use a yidam in our meditation and guru yoga. The yidam is an image that represents complete enlightenment to the meditator. Usually, it represents a being from the past or Buddhist mythology. Students choose an image they’re most comfortable with to represent their teacher and all the buddhas of all time.

I have used the three images above as yidams. Even a flower can represent all the buddhas. I’ve been told that we use yidams because we might get distracted by their flaws if we focus on our current human teachers. The yidams represent pure buddhahood.

This post was intended to share my thoughts about non-Buddhists becoming buddhas. I’ll leave it up to you to consider whether historical or current non-Buddhists might fall into this category.

As I wrote, I realized I was also explaining why I am a Buddhist. This is my chosen religion, and I hope its wisdom helps you in your chosen faith. That’s why I’m writing this blog, From the Pure Lane.

I hope you have found this blog post helpful. If you have friends who might enjoy it, please click the “share” button.

I’ll turn to buskers in the streets of Madrid for our musical bonus.

This is from the Anguttra Nikaya, as translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. I'll cite my sources because there are probably as many fake Buddha quotes as fake Lincoln quotes.