No words can describe it No example can point to it Samsara does not make it worse Nirvana does not make it better It has never been born It has never ceased It has never been liberated It has never been deluded It has never existed It has never been nonexistent It has no limits at all It does not fall into any kind of category. --Dudjom Rinpoche on the nature of mind

[This is a podcast version of a Substack I posted last week. My apologies for sending the text a second time.]

Thanks to my dharma friend and fellow blogger Chodpa for reminding me of that quotation in his September 25 blog post, which you can read in full here. You can follow him on Substack here. The obvious questions are:

If the nature of mind can’t be described or pointed to, why do we Buddhists use so many words, metaphors, and concepts to point to it? And why bother? Why should we know the nature of our minds?

Let’s take the second part—the why—first. Buddhism teaches that our minds work hard from our first year or two of development to convince us that we’re unique individuals who stand apart from others and who must prioritize our needs and wants. That might be a healthy stage to pass through as we mature, but our minds don’t want us to.

Our minds resist going from me to we—seeing how interconnected we are to all beings—because that would mean near-extinction for them. From the non-dual point of view, once we recognize that we swim constantly in the sea of oneness, we no longer need minds preaching to us about how special we are. We no longer need a grasping ego.

That grasping ego is our Mara, the Buddhist demon who represents the cycle (Samsara) of birth, death, rebirth, and dissatisfaction and whose mission is to divert us from enlightenment. Like so much in Buddhism, we can recognize Mara as a trait within ourselves rather than an external demon, or both.

Either way, Mara is the voice telling us that the route to happiness is more money, a new job, a new car, a new romantic interest, a new flavor of ice cream, a gold medal, even though we know we’ll soon want the next thing. He’s that voice telling us our life will be more satisfying if we don’t live in the same neighborhood as those people, if we refuse to listen to that point of view even though we remain dissatisfied with our lives no matter who or what we succeed in avoiding.

The way out of the cycle of dissatisfaction is to stop the craving and aversion, but we can’t simply order our minds to shut up our grasping ego. Instead, we each must get to know our mind and befriend it—or at least let it know we’re paying attention.

That’s the why, so we’ll turn to the how. “No example can point to” the nature of mind, but maybe one can help us understand why getting to know it is crucial.

Imagine living in a culture of arranged marriages, and you begin living with a spouse you hardly know. You say good morning to each other, prepare and consume meals, have intercourse, and say good night, but you long for a deeper relationship.

We can’t get to know our partners simply by knowing what time they awaken and go to sleep, how they cook and eat meals, or even how they have sex. We won’t know them until we feel we know their nature—not just in words and data but experientially, a sense of understanding that comes nonverbally over time. Maybe that’s the love experienced in successful marriages.

At the risk of taking the analogy too far, I’ll suggest that we want a successful marriage with our mind. If not a marriage, a successful relationship. We want to observe what it does without trying to restrain it or being controlled by it.

Words like those I’m writing might help nudge us in the right direction, but it takes more than words to find the path to knowing our minds. That’s where the chanting, rituals, and meditation taught in Vajrayana Buddhism help—and especially Vajrayana’s emphasis on the relationship with a teacher. For me, Lama Surya Das showed me the direction and Yongey Mingur Rinpoche, along with my daily practice and sangha, took me the rest of the way to feeling as though I made friends with my mind.

If you’re interested in an experiential learning track with a teacher I recommend for Westerners, I say more about that in the post below, based on my own experience.

How to Become Enlightened in This Lifetime

After three decades of practicing Theravada (foundational) and Mahayana (second wave) Buddhism, I was still confused about one thing. As far as I could tell, every form of Buddhism teaches that all beings have the Buddha Nature within or at least the potential for enlightenment, but it always seemed distant—not within reach.

And in my last From the Pure Land post, I wrote and recorded a guided meditation designed to offer a taste of the nature of mind. That’s here:

Finding Your Island of Refuge

What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun. —Ecclesiastes 1:9 English Standard Version

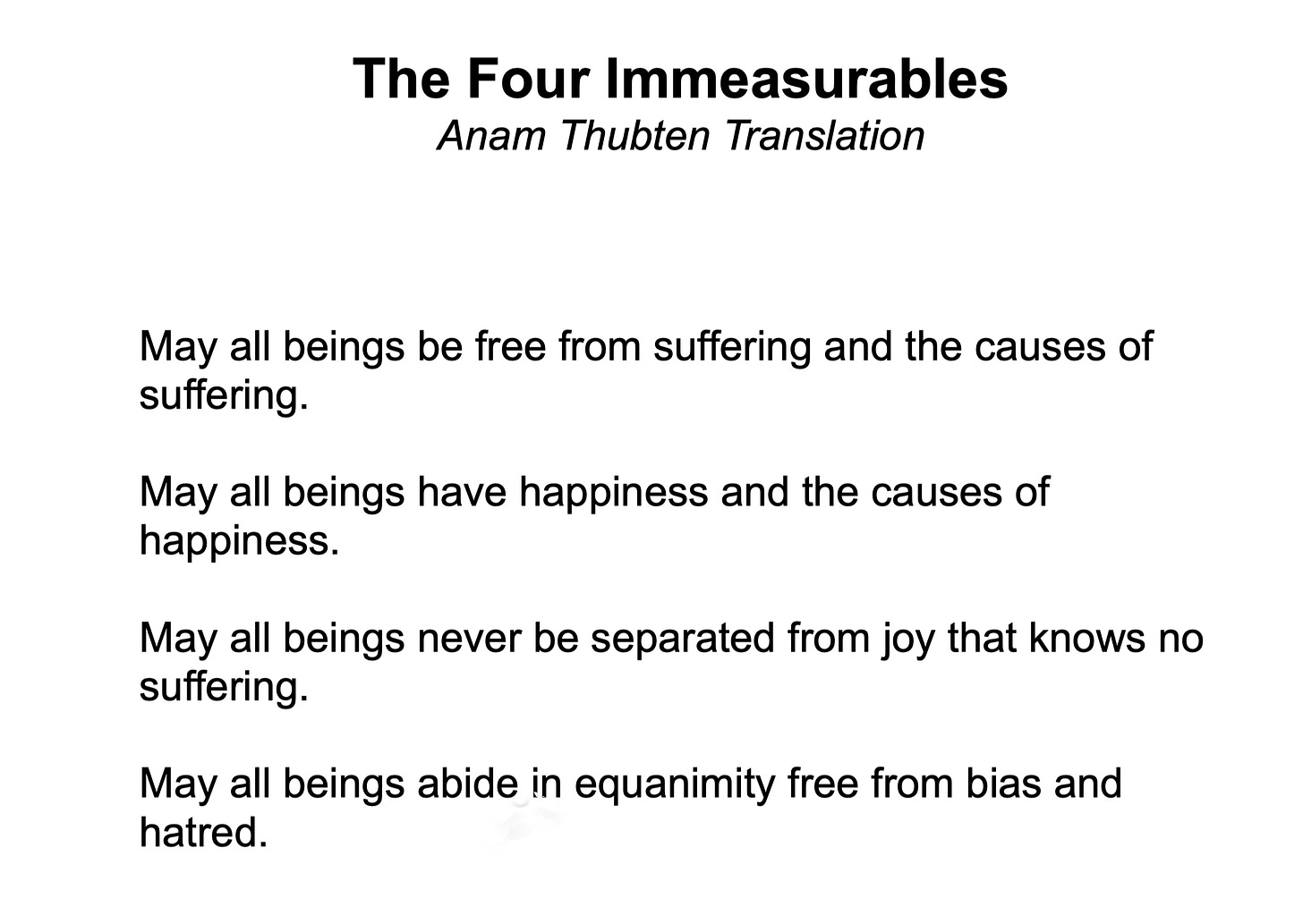

In closing, I share this prayer with you.

From the Pure Land has subscribers in 28 U.S. States and 11 countries. Consider:

Sharing this post with a friend.

Becoming a subscriber if you are not one already. Free and paid subscribers receive the same content, but subscribing for $5 a month or $50 a year helps support the mission.

If you prefer to make a one-time donation of any amount to support Mel’s work, click this button.

Share this post