Meet My Yidam, Amitabha

He represents compassion and presides over the Pure Land

A yidam or iṣṭadevatā is a meditational deity that serves as a focus for meditation and spiritual practice, said to be manifestations of Buddhahood or enlightened mind.

The Wikipedia entry for “yidam” begins that way, and I like the description. The idea of a deity in Buddhism can be interpreted in at least three ways, but not in the sense of a god who controls us. The deity is 1) an actual being existing in another realm and as an archetype in each of us, 2) an internal archetype that we may pray or chant to as though it’s external, or 3) both of the above.

I decline to engage in either/or thinking and select the third option, but that’s unimportant. What matters is whether having a yidam helps me relieve my suffering and the suffering of others. It does.

We initially envision the yidam as external because we’re conditioned to look outside ourselves for help and guidance. Vajrayana Buddhism teaches us a meditation practice called “guru yoga” or “deity yoga,” in which we choose a fully enlightened Buddha as our yidam, representing all enlightened beings. If possible, we meditate daily, beginning by calling to the yidam (often using the chant that’s the “musical bonus” below), envisioning it, and then absorbing the yidam into ourselves. The idea is to eventually become the deity, recognizing and resting in our inherent Buddha Nature.

For years, I picked a yidam almost randomly when doing guru yoga. I had trouble finding one image that resonated with me to represent all of Buddhahood. For a while, it was this stylized image of a lotus flower:

At other times, it was White Tara:

I decided on Amitabha as my keeper yidam partly because he is the creator and overseer of the Pure Land, where I strive to be reborn. I share my thoughts about the afterlife in this post:

If you think what I’m about to say is wacky, read the post for my reasoning, but here’s what I believe:

What happens to us after death is determined, at least in part, not only by how we live but also by the culture that formed our sense of reality and by our deeply held beliefs about the afterlife.

Chanting to Amitabha and incorporating his essence, along with my desire to come face-to-face with him in the Pure Land, makes sense. But I also love his image and his story.

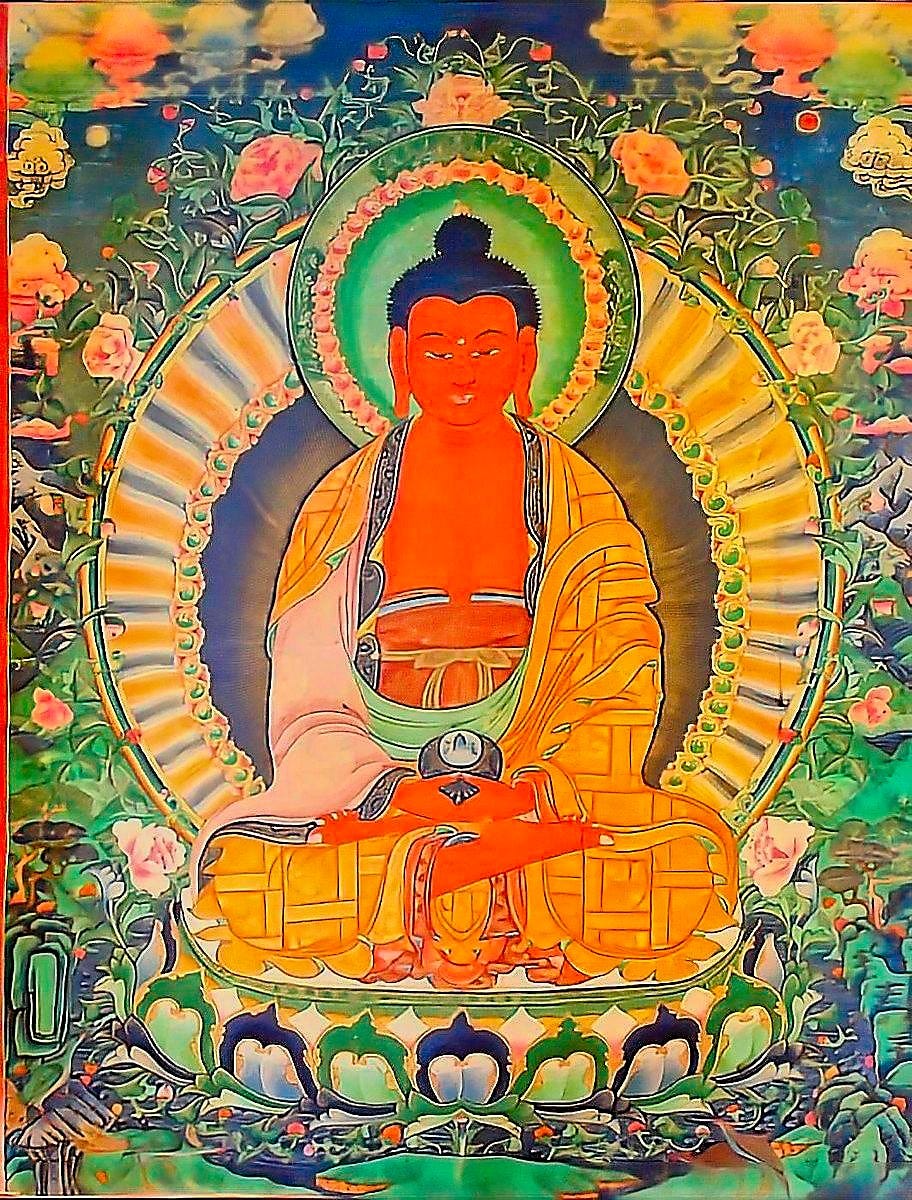

Here he is, as commonly portrayed in Tibetan imagery. His red skin symbolizes love and compassion. He sits in relaxed meditation with a begging bowl in his hands, surrounded by illuminated colors and flowers. The “begging” bowl might instead be called a “generosity” bowl. Among other things, it represents his ever-present willingness to help beings achieve Buddhahood.

Amitabha represents compassion and the possibility of liberation for all beings.

Two concepts from Buddhist mythology will help you understand Amitabha’s story:

As I’ve explained here, in Buddhism, just as people are reborn, so are worlds. Each world's life cycle is called a kalpa and lasts for billions of years. One or more Buddhas may manifest in a kalpa. We live in the kalpa of the Buddha who started this life as Siddhartha Gautama.

When Buddhas pass into parinirvana, as Gautama Buddha did at age 80, they may decide to and have the ability to create a Pure Land, a celestial realm completely or essentially free from suffering and impurity.

Here’s Amitabha’s story:

Many kalpas ago, he was a human king who renounced his throne to become a monk named Dharmakara. Deeply moved by the suffering of beings, Dharmakara made 48 vows before the Buddha of his kalpa. He vowed that he would only accept full Buddhahood once he had created a Pure Land welcoming to all who called out to him with a sincere heart.

It took Dharmakara countless lifetimes over additional kalpas to amass the positive karma he needed. Still, he finally became Amitabha Buddha and established the Western Pure Land, also known as Sukhavati—a realm free from suffering—where beings could be reborn and easily attain enlightenment. This is the land generally called the Pure Land. Buddhists will typically clarify when referring to another Pure Land created by another Buddha.

Buddhists worldwide venerate Amitabha, but he is central to Pure Land Buddhism, which is most prominent in East Asia but is well represented globally. Devotees believe that by having faith in Amitabha and reciting his name, they can be reborn in his Pure Land after death. Shin Buddhism is a widely practiced form of Pure Land with a strong network of temples in the United States.

Here’s a description from Shin’s Buddhist Churches of America website:

Shin Buddhism focuses on a lay-oriented, non-monastic approach to Buddhism. This is both easier and more difficult at the same time. Although there are no monastic precepts to follow, nor arduous meditational practices to do, our everyday life becomes our “practice center.” We must struggle with work, relationships, child-rearing, caring for elderly parents, and the myriad experiences and responsibilities of our lives.

In Vajrayana Buddhism, Amitabha is one of the Five Tathāgatas, which are essential in iconography (especially mandalas) and the faith’s ontology. As for the Pure Land, Vajrayana teachers tend to coach their students toward full enlightenment, which may take more rebirths in the human realm. With every rebirth, the student will work to spread the dharma and get closer to full Buddhahood.

You might call rebirth in the Pure Land an optional variant. If you…

focus your efforts on that next life,

chant and pray to Amitabha,

practice generosity, wisdom, virtue, joyful effort, patient forbearance, determination, goodwill, honesty, equanimity, and non-attachment to worldly distractions,

dedicate your possessions and your achievements to others,

and maintain awareness through the death process,

…Amitabha will hear you proverbially knocking on the proverbial door and let you in.

Once in the Pure Land, you won’t be reborn in the human realm and will be surrounded by Buddhas, other deities, and bodhisattvas who will guide you toward full enlightenment.

At 78, I’ve studied and contemplated teachings about a good death, and I’ll do what I can to have one. Moving smoothly to the Pure Land, as I understand it, is as good as it gets for me. Since I believe that thought creates reality, I believe I have a good shot at it.

If I’m wrong, I’ll still go out smiling and having left a trail of loving-kindness.

May we all end this lifetime as we wish to.

Emaho!

From the Pure Land is read by subscribers in 25 US states and eight countries.

If you have found this blog post helpful, whatever your religious path, please share it with your friends.

All subscribers, free or paid, get the same From the Pure Land content. Paying for your subscription is a way of supporting my work. From now until the U.S. Labor Day on September 2, paid subscriptions are discounted by 40% for the first year. So they’re $3 a month or $30 a year. Click here or on the button below to ensure you get the reduced rate. After a year, if you don’t end your subscription, it will renew at the $5 or $50 rate. However, you will only get the reduced rate for your first year if you subscribe by September 2.

Whatever you decide, you’re supporting my work simply by reading it.

Our musical bonus is the beautiful “Lama Chenno” chant, calling to our guru. It is often used as a prelude to envisioning and absorbing our yidam.

🙏🙏