All thoughts and feelings that are produced by the mind become dirt after they have been produced. The mind that remains attached to these external things Is dirty. Wash out, wash away all this dirt. The naked mind, mind as such, is the most clean, pure, beautiful mind. It doesn't cover itself with ornaments or patches: This mind as such is the truth and is clean and pure. This is what we call the true mind or the pure mind or the single mind or the real mind. This mind, not covered with ornaments or patches, is the strongest thing in the world. This true mind, naked and as such, is the most beautiful thing in the world.

"The honest mind is the Pure Land." This is it.

Before I say more about that quotation, some background on what it means to me, how I found it, and who wrote it. My practice has been primarily influenced by:

Thich Nhat Hanh and other Mahayana and Theravada teachers I studied with beginning in the mid-1980s. I avoided Vajrayana, or Tibetan, Buddhism because I considered it too esoteric and ritualistic.

Lama Surya Das, who showed me at the start of 2016 that Vajrayana teaches what I had come to believe—that enlightenment is within reach for us within one lifetime.

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, who I now consider my primary teacher. He led me to what I call making friends with my mind, which is the essence of enlightenment.

Andrew Holecek. His book Preparing to Die and a retreat I did with him showed me how to incorporate the Pure Land into my Vajrayana practice.

A pure land is what’s known as a Buddha realm, manifested by a buddha who has left the human realm. Buddha Amitabha manifested a pure land called Western Pure Land, also known as Sukhavati—a realm free from suffering—where beings could be reborn and easily attain enlightenment. I wrote more about that here:

Meet My Yidam, Amitabha

A yidam or iṣṭadevatā is a meditational deity that serves as a focus for meditation and spiritual practice, said to be manifestations of Buddhahood or enlightened mind.

For everyone—but especially those my age—preparing for death is an essential part of practice. I co-meditate with Amitabha and aspire to be reborn in his Pure Land daily. I have heard Mingyur Rinpoche endorse the idea that rebirth in the Pure Land is a reasonable goal for Vajrayana Buddhists.

Andrew Holecek adds (and I wouldn’t surprised if Mingyur Rinpoche agrees) that, since mind creates reality, we already live in a pure lane as long as we awaken to it. Once we are certain that we already live in a pure land—once we really live that way—the move to Amitabha’s address upon death will be easier. We die as we have lived.

The Pure Land School of Buddhism centers on Amitabha’s vow to accept into Sukhavati anyone who sincerely calls out to him. From my Vajrayana perspective, it’s important to make friends with my mind as well as to venerate Amitabha. I haven’t said anything about living ethically with loving-kindness and compassion, but that’s an implied part of the deal.

When I die, if it turns out I was wrong, I will still have made a contribution while alive and will go out smiling.

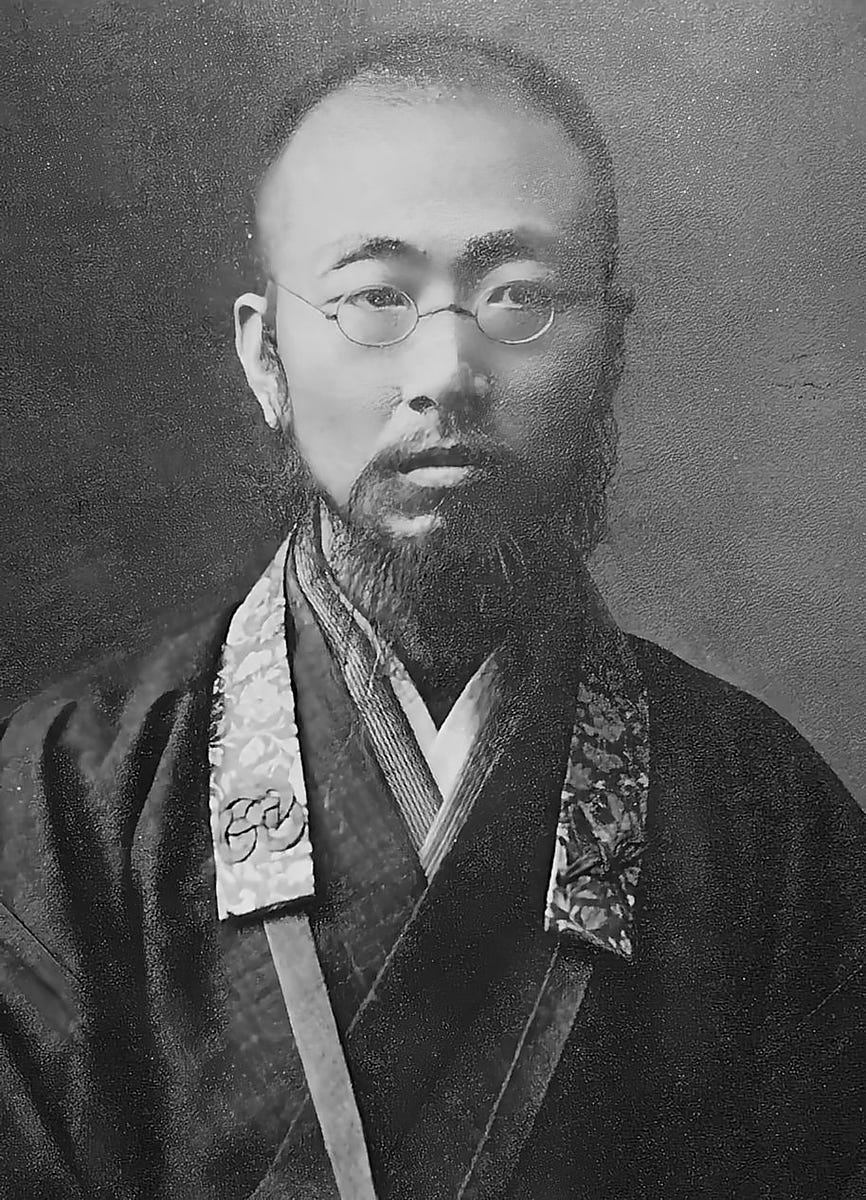

It was through a new dharma friend I’ll call Charlie that I found the quotation at the start of this post. As he and I got to know each other via the Substack Chat feature, we realized that our very different paths had brought us to the same praxis—a practice involving both Vajrayana nature of mind and Pure Land. He introduced me to an obscure minister, poet, and author named Haya Akegarasu (1877-1954), who despised labels like minister, poet, and author.

Have I mentioned that he’s a maverick?

If you reread the quotation, you’ll see that Akegarasu comes to a conclusion like Charlie’s and mine. I’d express it something like this:

The Pure Land and the true mind are one.

I’m just learning about Akegarasu, but his life and mine share some similarities: His father’s death when he was ten, my father’s when I was eleven, and the traumas we both suffered in middle age were major influences on our spiritual development. We are both iconoclastic and outspoken, although he may outdo me a bit there. (I’m working hard to catch up.)

We both put in decades of practice before finding a path of our own. The story of Amitabha—which I summarize in the link to my previous post above—inspired him and inspires me.

Akegarasu began a lineage in Pure Land that appears to be dying, but who knows? Maybe Charlie and I can give it a nudge. Very little of Akegurasu’s writing is available in English, but I hereby vow to see what I can do about that once I have completed work on my The New Middle Way: A Buddhist Path Between Secular and Ossified.

One more thing about Akegarasu. He was a Pure Land practitioner of what, in Vajrayana, we call crazy wisdom. This is the idea that highly realized teachers sometimes use provocative, nonconforming means to jolt students out of their conceptual thinking. I suspect that some of the ancient stories about crazy wisdom that seem cruel now have been exaggerated as they were told and retold over the centuries, but the concept is what matters.

A more recent practitioner of crazy wisdom, and one of my faves, is Patrul Rinpoche (1808-1887). Matthieu Ricard’s book of Patrul stories, Enlightened Vagabond: The Life and Teachings of Patrul Rinpoche, is an enjoyable read.

I suspect that what has been said about Patrul Rinpoche goes for Akegarasu as well:

Although some people were wary of him because he communicated very directly and could be very unflattering, he was unfailingly kind.

From the Pure Land has thousands of readers and subscribers in 40 U.S. states and 21 countries, and the podcast has thousands of listeners in 55 countries.

Consider the generous act of paying for your subscription even though you’ll receive the same regular content as those with a free subscription. For $5 a month or $50 a year, you’ll contribute to Mel’s expenses and see parts of his book The New Middle Way as it progresses.

Share this post with a friend.

Give Mel a one-time “tip” of any amount.

Listen and subscribe to the From the Pure Land podcasts via your favorite app or by clicking here.