Being One With Everything Is Not Being John Malkovich

It's shedding ego and recognizing the interconnectedness of all things

An opinion article in the Scientific American blog with the headline Don’t Make Me One with Everything captured my attention. In it, John Horgan, author of Rational Mysticism, argues:

Do we really want to live in a world in which there is no other? There are no selves but only a single Self? Is that heaven or a solipsistic hell? Isn’t some separation from ultimate reality necessary for us to appreciate it?

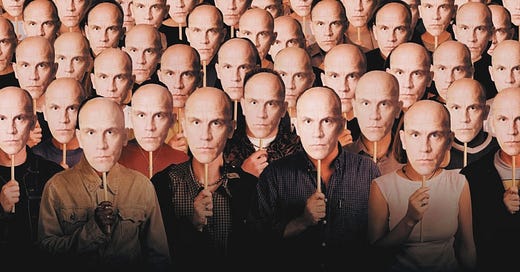

Horgan goes so far as to suggest that a world of oneness would be similar to the film Being John Malkovich, which includes a reality where everyone wears Malkovich’s face and repeatedly says his name.

In a psychedelic trip in 1981, Horgan says, he…

…became the only conscious entity in existence…. It started out as a good trip, but then it became very bad. I felt excruciating loneliness and fear. The trip convinced me that the reduction of all things to one thing is a route not to cosmic consciousness but to unconsciousness, oblivion, death. One thing equals nothing.

The science journalist’s idea of oneness at first seemed totally mistaken, at least from my Buddhist perspective, but as I thought it through, I began to see what he was suggesting. I don’t agree, but let’s explore it. I have no credentials as a Buddhist teacher, so what I write is my reflection on the teachings and my experiences.

A Secular View

We live in a sea of molecules, atoms, subatomic particles, and waves that scientists believe all originated from the Big Bang. Everything we can perceive is made of these. A minuscule portion of those formed to make you, another portion to make me.

Some combine to make the air around us, the tree across the street, the house we live in, the pet sleeping on our floor, the animals in the jungle, the fish in the sea, the jungle and the sea, the Earth and the planets, the sun and the moon, and the entire universe that we’re aware of.

None of this is static. We shed tiny bits of ourselves into the air around us and the articles we touch, and we absorb some tiny bits from them. The correct quantum term for the tiny bits is in some dispute (particles, waves, or fields), so we’ll call them stardust. For almost 14 billion years, our scientists tell us, the same stardust arranged and rearranged itself to create the current moment, and the dance goes on moment by moment.

The result is an interconnected universe, but let’s bring it down to daily life. The air I breathe is interconnected with the air you breathe. The eggs I ate for breakfast are connected with the trip I made in my car—powered in part with energy that came from the sun—to the grocery store, the workers who stocked the shelves, the truckers who transported the eggs, the chickens who laid them, the feed they ate, the farmer who raised them and harvested the eggs, the sun, wind, and rain that provided the environment, and on and on.

Whether we think about dancing stardust or what I ate for breakfast, we live in a world in which everything is so interconnected that it may as well be considered one entity. I don’t need to be the same as the chicken in order to be one with it.

Adding the Spiritual

Because I am intimately interconnected with everything else, and because both my mind and my body change from moment to moment, do I really have a discreet, lasting self? The egg I ate for breakfast had changed form several times: from embryo to laid egg, from laid egg to cracked egg, from white and yolk to scrambled, from raw to fried, and on into my mouth and digestive system. Part of it provides the calories I’m using to keyboard these words. It’s easy to see that the egg had interconnectedness but no discreet, lasting existence.

Then there’s the question of perception. The embryo and fetus that became me existed as one with the mother. After birth, when the baby I think of as me first opened its eyes, it had no sense of a self separate from everything else. It took “me” around 18 months to decide on the terms of the separation. That was a necessary learning process to survive in this world we live in. I had to learn my limits and your limits. I had to learn that I can’t walk through you or the wall.

But…

Buddhist wisdom (and that of some other religious disciplines) holds that we take the separation too far. Our ego is never satisfied with our being an ever-changing collection of stardust in a stardust universe. It encourages us to cling to a sense of self—a self that wants more stuff and status to make itself special and happy, even though stuff and status are never enough.

Much of Buddhist practice is about remembering the oneness. But does that mean we all merge into “one thing,” as in Horgan’s bad psychedelic trip? For the answer, let’s first consider the Two-Truths Doctrine, as explained in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Knowledge of the conventional truth informs us how things are conventional, from the ordinary commonsense perspective and thus grounds our epistemic practice in its proper linguistic and conceptual conventional framework. Knowledge of the ultimate truth informs us of how things really are ultimate, from the ultimate analytical perspective and so takes our minds beyond the bounds of conceptual and linguistic conventions. (Emphasis added.)

What the encyclopedia calls conventional truth enables us to live in the world as we perceive it. Ultimate truth is how the world really is, with me, the house I live in, and the tree outside being one. Conventional truth prevents me from trying to walk through the walls of my house and through the tree. Ultimate truth is an experiential understanding of oneness that can’t be expressed in words.

As long as I live in the conventional world with its conventional truth, John Malkovich and I are one because of how interconnected we are and because we both have Buddha Nature, but we are not the same. We’re like two cups of water taken from the same stream.

I can’t tell you what it’s like to live full-time in a Nirvanic state of ultimate truth, but I believe that I’ll shed ego and clinging along with attachment to a body, but not every sense of identity. My vision is that I’ll still be a cup of water in a sea of oneness, but maybe the container that holds me will be more porous.

I have never been there on a psychedelic trip, but I may have touched it briefly once in meditation. I have no fear of it.

From the Pure Land has thousands of readers and hundreds of subscribers in 32 U.S. states and 14 countries. The podcast has listeners in 35 countries. Consider:

If you are not already a subscriber, please become one. Free and paid subscribers receive the same content, but subscribing for $5 a month or $50 a year helps support my mission to reduce the world’s suffering.

Make a one-time gift of any amount.

Share this post with a friend.

Listen and subscribe to the From the Pure Land podcasts via your favorite app or by clicking here.